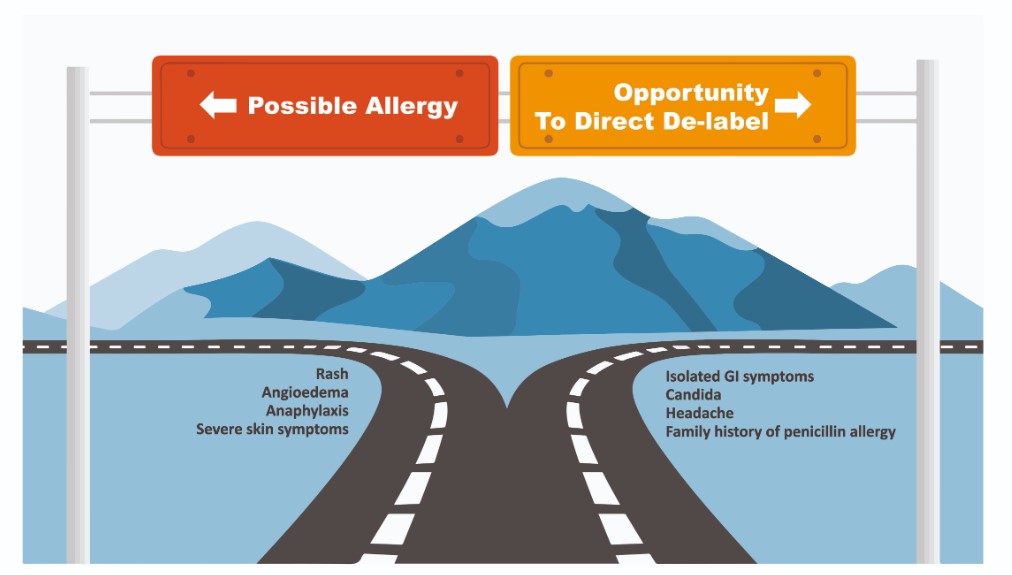

Figure 2: Identifying possible allergy and opportuities to de-label

Many patients can be directly de-labelled through a focussed history alone. A good history helps effectively stratify risk in patients that need immunology assessment (see ‘Referral to an Immunologist’ section).

Penicillin allergy is not an inherited disease. Patients reporting penicillin allergy due to a family history should be directly de-labelled.'

A simple allergy history (as above, Section 1.1) may allow identification of clearly non-allergic symptoms.

Direct de-labelling is appropriate when the reported symptoms include:

- Nausea or other isolated gastrointestinal symptoms

- Headache

- Mucosal candidiasis

- Patients reporting penicillin allergy due to a family history

In these instances it is appropriate to directly remove the allergy label without need for further assessment. Patients can be told that the history is not in keeping with penicillin allergy and that there is no need for them to avoid penicillins in the future. When de-labelling penicillin allergy, update all healthcare records (e.g. GP, pharmacy, dentist, etc.) and communicate this change to other healthcare providers. Ensure the patient clearly understands the change in their allergy status. It may be useful to communicate this in writing to all parties involved.